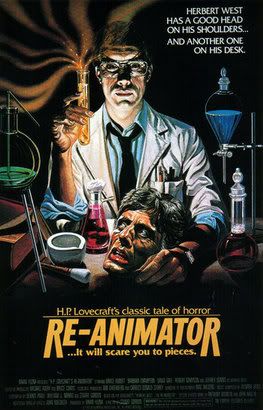

My embarrassing horror-geek confession to you, dear reader, is that I have never really read Lovecraft. I know, I know. It goes against everything logical. I’m supposed to be a huge fan of King, possibly a loyal fan of Barker, and most certainly an obsessive Lovecraft fan—an obsession I should have started cultivating since at least junior high. I actually knew this at about that time, and I gave Lovecraft a shot. Whatever the reason, he didn’t take, and I didn’t pick him up again until a couple of years later, when I was turned on to the Herbert West – Reanimator stories. I don’t recall what my reaction was at the time was, except that I, of course, loved the movie. I’m happy to say that this month’s topic here at The Zombie Blog has prompted me to re-read the stories. I couldn’t be happier with the timing; after years of loving and getting to thoroughly know the zombie sub-genre, and having been around long enough to witness certain arcs and dips in its history, I’m glad to have this perspective when re-evaluating these stories anew.

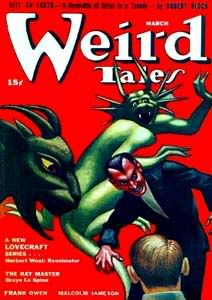

The Herbert West – Reanimator stories were originally published in 1922, in Homebrew magazine, under the title of “Grewsome Tales.” Seabrook’s The Magic Island was still seven years away from introducing the Haitian zombie to Hollywood in 1929, and White Zombie was still ten years away from introducing this same zombie type to filmic audiences. This is extremely interesting in the sense that, I believe, after reading Lovecraft’s undead contribution, these six stories indeed encapsulate the entire history of the zombie film sub-genre—from their humble beginnings right up to the very present. They even usurp Mr. Romero of the much-claimed title of the man who introduced cannibalism to the zombie mythos.

In Story I, From the Dark, the quivering, screaming result of West’s scientific trial exhibits only rudimentary memory—and not even of its past life. West and his assistant, the narrator (whose name we never know, but who we come to know as Dan Cain in the films), undertake the reanimating experiment, and it ends in what they perceive as failure. When they go to another room of their secluded farmhouse to concoct another batch of the reanimating fluid (assumed to be faulty), a ghastly scream is heard, which frightens them into abandoning the farmhouse. The following day, they read in the paper, in two separate articles, that the farmhouse had been burnt to the ground and the grave out of which they retrieved the poor soul bore evidence of a failed attempted to crawl back in. Who knows how the farmhouse burnt down, but the fact that this monster obviously tried to find its way back into its own grave leads one to believe that it retained some kind of memory. It’s true that there’s no logical sense to this at all. One could understand memories of the previous existence, but from death until reanimation, there would be no way to it to form memories. Hence, how did it know where its own grave was? Nevertheless, this can be used as an example of some kind of conscious activity, which even Madge Bellamy is able to exhibit towards the end of White Zombie. Here we have the start of the zombie in film.

Story II, The Plague-Demon, is where Romero’s critical claim to cannibalism is toppled. West and company are at it again, during an epidemic which kills Dean Halsey, of the now infamous Miskatonic University. Of course he is reanimated, and the result is his mindless murderous rampage (a rage reminiscent of the 28 Days Later “infected”), killing many people…and eating them. It’s mentioned ever-so briefly: “It had not left behind quite all that it had attacked, for sometimes it had been hungry.” This single line is so subtle it’s as if a meaningless side note—Lovecraft could never have known what an integral piece of the sub-genre this would come to be, let alone have any inkling that there would be an undead movement at all! Halsey’s zombie form is merely a ravaging automaton, killing instinctually, for seemingly no real reason, and only eating its victims when it felt like it—when it was hungry.

This is repeated in Story III, Six Shots by Moonlight. Here the revitalizing duo have brought back Buck Robinson, aka “The Harlem Smoke”, who was accidentally killed during an illegal boxing match. Of course, his corpse doesn’t respond soon enough and he’s discarded as a failure, and buried in a shallow grave. Later, an Italian family is missing a small boy and all hell breaks loose. Somewhat predictably, this third zombie edition shows up rattling at the back door, with the boys arm in its mouth, suggesting the fiend had feasted on him. He is, of course, shot six times by West. These last two tales have brought the zombie up quickly from White Zombie in 1932 to Romero’s Night of the Living Dead in 1968, which is quite a jump. The missing years are negligible though, considering how forgettable most zombie films were in between.

Stories VI and V take up where Night left off in the evolution of the zombie, just as Dawn of the Dead and then Day of the Dead did. The zombies are learning, or at least, they are exhibiting some specific signs of memory. In both cases, the first thing the newly undead creatures find themselves doing is screaming in reaction to something that happened the moment they died. Story VI, The Scream of the Dead, the zombie exclaims “Help! Keep off, you cursed little tow-head fiend – keep that damned needle away from me!” Of course, the tow-head fiend is West, and he’s been up to no good, much to the horror of his assistant. In Story V, The Horror from the Shadows, the reanimation victim, Major Sir Eric Moreland Clapham- Lee, was nearly decapitated (a job that was finished once West and friend got a hold of him) when his helicopter, piloted by Lieutenant Ronald Hill, crashes during the Great War—where our two doctors are serving; the closer to the action, the fresher the specimens (obviously inspirational to the opening scene of Bride of Re-Animator). Major Moreland Clapham-Lee’s body awakens from The Big Sleep, with it’s head on the other side of the room hollering “Jump, Ronald, for God’s sake, jump!” Next thing they know, a shell explodes near them, chaos, and what becomes of the Major’s body is not known...until the next and last installment of the series.

These last two stories, V & VI, clearly show some signs of progress being made with West’s experiments, as he’s able to access fresher samples with which to experiment on. Regarding the always lively debate in zombie film circles as to whether or not the brains of the zombies function at all, and whether or not they are capable of learning or emotion, these two Lovecraftian examples of the undead are comparable to the shopping mall zombies of Dawn, who retain enough of their past-life memories to return to the shopping structure to begin with, and also to Bub in Day, who demonstrates his own ability for recall in the memorable scene with Dr. Logan, as he explores the Walkman, the razor, the book, and then later, the gun. Bub also shows us the capability zombies have for emotion—the fondness for Dr. Logan, and the hatred for Captain Rhodes.

Finally, Story VI, The Tomb-Legions, brings us up to date, and quite rapidly. In it, Major Moreland Clapham-Lee has returned, as is collecting all of West’s past experiments that are available (it’s also not entirely clear if his small, but growing army of the undead is all a result of West, or if it’s somehow generating more undead on its own), including the cannibalistic Halsey from the second installment, in order to enact some kind of revenge. This, very obviously, takes a kind of reasoning skill that none of the undead has exhibited until this time. The leap in intelligence from Story V to Story VI is about as drastic as the jump in the same matter from Day of the Dead to Land of the Dead. In Day, Bub shows not just mere memory, but also small signs of active learning (and his affection for Dr. Logan), and in Land, Big Daddy leads an army of undead through various undertakings and maneuvers (and his resentment towards the living). Also, the undead Cholo character knows enough—almost immediately after reanimation—to dispatch of the Kaufman character in a most complicated way (that is, complicated by zombie standards). There is the acquisition and retention of knowledge and there is the want of retribution, as well as its execution.

Far from merely inspiring a well-known and generally well-loved modern zombie flick, ReAnimator—years before Romero came onto the scene to so dramatically change the sub-genre; even at least a decade before the zombie itself came into the public’s consciousness—Lovecraft managed to foresee, in six short and simple stories, the historical timeline of the popular zombie in film, from its beginning to the present state of things; from the somewhat directionless undead automaton to a thinking, planning, and ultimately vengeful thing of horror.